|

|

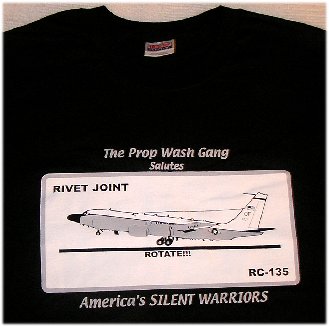

I usually don't wear T-shirts that bear logos and printed messages, but I have one on this morning with an airplane across the front.

It is a silvery-gray Air Force RC-135 just as its main gear clears the runway. With the image spread across my chest, I can hear and feel the powerful jets scream as they lug the heavy aircraft into the air.

It is heavy because it is packed full of communications gear - radio receivers, tape recorders and antennas - and a crew of guys like me.

It is so heavy that it cannot take off with a full load of fuel. It will hook up with a tanker and take on more fuel before it heads off to "the sensitive area."

It is the height of the Cold War, and the plane is on its way to the Soviet Union, where it will skirt the border for several hours, collecting communications intelligence.

It's been 30 years since I hunched in the backend of this aircraft, squeezing my headsets to hear every syllable of what a Soviet fighter pilot flying alongside might have to say, but his voice still rings clear in my head.

And just as clearly, the voices and the faces of my crewmates come back to me. I often play them back in my memory, where they are still young and strong, and I am, too.

Add some wrinkles and some gray hair - 30 or 40 years of each - and you have a gaggle of geezers from across the United States who gather every year to renew the bonds formed in the backend of those blessed airplanes.

The group is known as the Propwash Gang, named for the wake left by the propellers of C-130s we used to fly before many of us changed over to the big jets.

My wife and I spent part of last week in Destin, trading lies and toasting the old days with old friends from the Propwash Gang, and she bought me this T-shirt.

Unlike a finite group, such as a high school class, whose reunion grows smaller every year, the Propwash Gang still is growing. It has members who flew B-50s at the end of World War II and members who are still flying in Iraq today.

I spent most of my time in the European Theater, where the target languages were Russian, Czech, Polish and others of the Soviet Bloc.

Others flew mainly in the Far East, where the languages were Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese and Russian.

Wherever we flew, we depended on the Morse operators who plotted us and the fighters from enemy radar stations, and on the maintenance technicians who kept all our equipment running.

All these people make up the Propwash Gang. While I logged just more than 2,000 hours in the C-130s and 4,000 hours in the RC-135s, some of our guys flew 12,000 to 14,000 hours, and some of them still are flying.

The gang got organized over the Internet as part of an effort to dedicate a C-130 in a memorial park at Fort Meade, Md.

The plane, which was put on display in 1997, was repainted and fitted with three-bladed props to look like 60528, which Soviet fighters shot down over Armenia in 1958 with a crew of our guys on board.

That was before my time, so I didn't know any of 528's crew, but I flew with guys who did. The connection we all feel with that crew and other crews we lost still is strong.

The Propwash Gang is the airborne component of a larger group known as the Silent Warriors, who gathered communications intelligence in the air, on the ground and at sea.

When they raised their glasses and revved up their stories in Destin, it would have been difficult to think of the old warriors as silent. The cacophony would have rivaled any airplane they ever flew on.

This was my first reunion, and I thought I'd better go while I still could. Many of the guys I flew with have died in the years since I last saw them. More could turn in their gear before we gather again next year in Omaha.

That's why I wanted my wife to meet the gang and hear the stories. And why she wanted me to have this shirt.

Darrell Norman is a staff writer and columnist for The Gadsden Times. His e-mail address is daxnorman@mindspring.com.